The story of Henry Box Brown’s escape from slavery

Denise Valentine doesn’t so much tell the remarkable story of Henry “Box” Brown, an escaped slave and abolitionist who mailed himself to freedom in 1849, as she sings, chants, and stomps it. A professional storyteller and Commonwealth Speaker for the Pennsylvania Humanities Council, Valentine uses the folktales and handclap games of African-American oral tradition to animate her discussions of the Underground Railroad and the heroes of black emancipation. “The historians take care of the facts and figures, the dates and the statistics. But I try to help people understand what it felt like,” she says. “What it was like to be an African American living during the time of enslavement, what it was like being a white person trying to help an African American escape, or even what it was like to be a slave owner or merchant.”

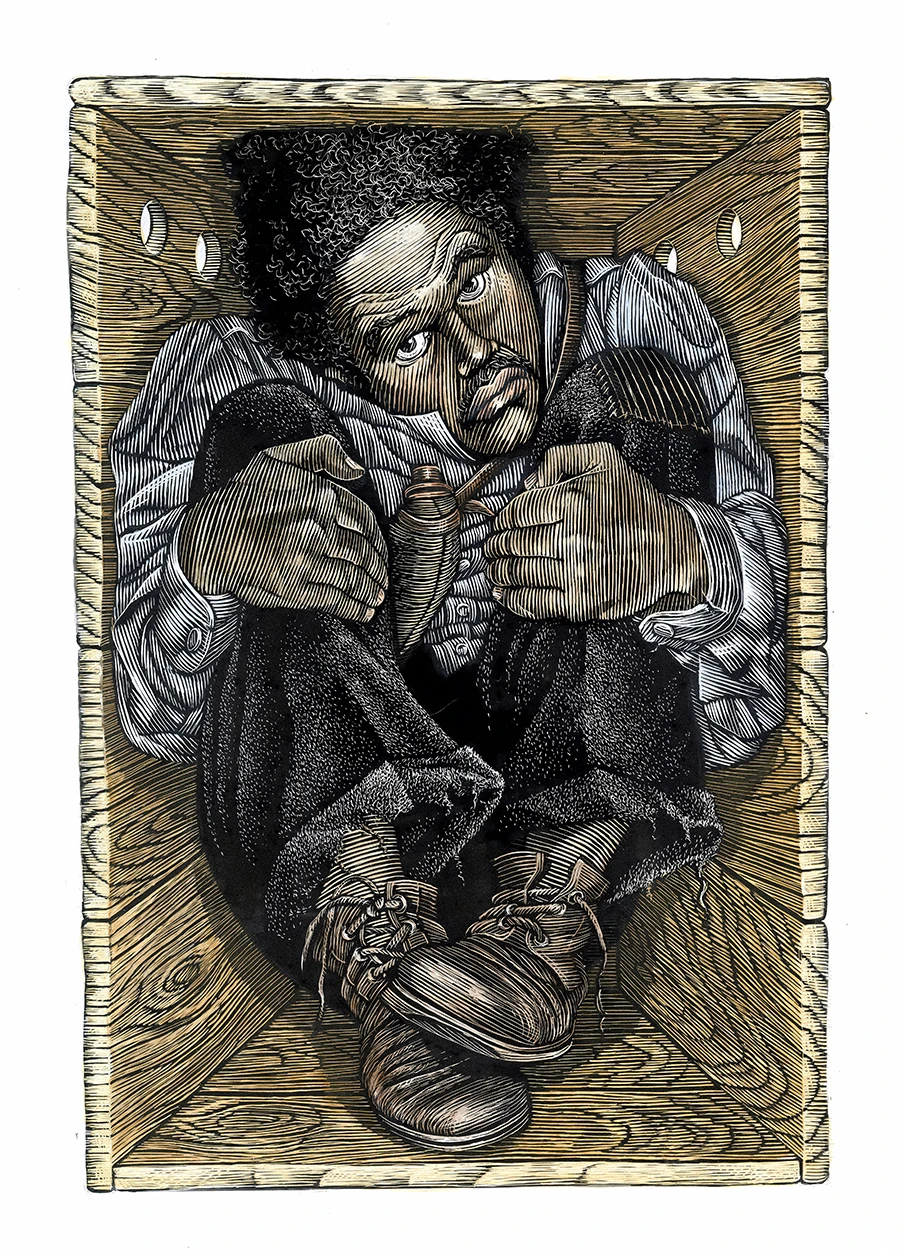

Her colorful reenactments are at least partially indebted to the bravura style of one of her famed subjects: After a grueling, twenty-seven-hour voyage from Richmond to Philadelphia in a tiny wooden container, Henry Brown found a lucrative career as a public lecturer in the North. His means of escape became part of his identity when he was rechristened “Box” Brown at a Boston antislavery convention.

Appearing in cities across New England and, later, Britain, Brown attained a form of nineteenth-century celebrity on the strength of his astonishing tale and flair for showmanship. He rode between speaking engagements inside a box identical to the one that had carried him from Virginia, accompanied by marching bands and American flags, before emerging onstage from the cramped conveyance and presenting scenes from his “Mirror of Slavery,” a painted canvas of one hundred scenes mounted on two enormous spools. Various iterations of the act, which evolved into a kind of vaudeville routine following the end of slavery, were performed in the United States, England, and Canada for decades before Brown receded from view, dying sometime after 1889.

When she was a student, Valentine remembers, “I did mandatory tours of historic Philadelphia . . . and I remember feeling like my story was not told in any of these places. I remember wondering, ‘Did African Americans contribute anything to the founding of this country?’ Where was our story? And I went searching for it.”

The route through Philadelphia was perhaps the busiest line of the Underground Railroad, and Valentine’s investigations into its legacy led her to dig through centuries of neglected history—from the arrival in 1684 of the city’s first shipment of human cargo to the very literal excavation of slave quarters in the rediscovered foundations of the President’s House in 2002. The long-demolished building, which functioned as the Presidential Mansion during Philadelphia’s decade as the nation’s capital, also housed George Washington’s domestic staff of nine slaves.

The men and women who attended to the first family—maids and stable hands, scullions and cooks—were regularly shuttled back and forth between Philadelphia and the Mount Vernon estate; this migration allowed the president to get around Pennsylvania’s Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, which granted any slave their freedom after inhabiting the state continuously for over six months. Among the first stories that Valentine told professionally was that of Oney Judge, a dower slave of Martha Washington who bolted to New Hampshire in 1796 rather than return to Virginia and the possibility of being given as a wedding present to the first lady’s granddaughter.

There have been several depictions of Henry “Box” Brown’s unlikely flight from bondage (including a play by Tony Award-winning author Tony Kushner), the first of which was provided by Brown himself: His 1851 Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown offers both a moving account of his life in servitude and an extremely bitter harangue against the greed and false piety of slave holders. A favorite of his master, the successful planter and Richmond mayor John Barret, Brown was seldom subjected to the extreme deprivation and violence that haunted the lives of most slaves. His comparatively fair treatment, however, afforded him no peace of mind. “The slave has always the harrowing idea before him—however kindly he may be treated for the time being—that the auctioneer may soon set him up for public sale and knock him down as the property of the person who, whether man or demon, would pay his master the greatest number of dollars for his body,” he wrote.

Ultimately, Brown was never sold—his wife and children were. Grief-stricken and powerless to protest, he enlisted two friends to enclose him with a small supply of water inside a 15-cubic-foot box (about half the size of a casket) and ship him to the headquarters of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Transported by wagon, railroad, and steamboat, the box was flipped upside down for so long that its passenger worried his skull might burst, and only arrived at its destination after a full day in transit. Brown arose in freedom from what he called “the grave of slavery,” ready to begin telling his story. He never saw his family again.

/About the author

Kevin Mahnken is an editorial intern at HUMANITIES.

Article appears in

HUMANITIES

May/June 2013

Volume 34

Issue 3

70-140cm (27.5″≈55″) Printable

70-140cm (27.5″≈55″) Printable